Griffiths Land Valuations Explained

What is Griffith's Valuation?

Griffith's Valuation is the name widely given to the Primary Valuation of Ireland, a property tax survey carried out in the mid-nineteenth century under the supervision of Sir Richard Griffith. The survey involved the detailed valuation of every taxable piece of agricultural or built property on the island of Ireland and was published county-by-county between the years 1847 and 1864.

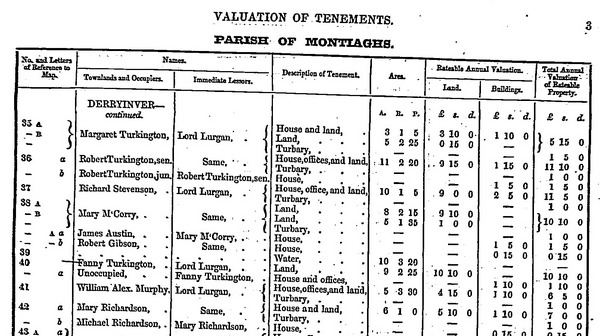

The process of valuation was painstakingly thorough, involving multiple visits by valuation teams to analyse all of the factors influencing the economic status of the property: the chemical and geological properties of the land; average rents paid in the area; distance from the nearest market town. The aim was to get as accurate as possible an estimate of the annual income that each property should produce. This is the 'Net Annual Value' figure (in £ s d, pounds sterling, shillings and pence) in the far right column of each valuation record. This was then used as the basis for local taxation, and continued up to the 1970s. The local authorities decided on a percentage of the Annual Value to be paid every year and usually expressed as pennies to the pound. For example a rate of 3 pennies to the pound meant that someone in possession of property valued as £10 would have to pay 30 pence, or 2/6.

The individual in economic occupation of the property was responsible for payment of the local taxation based on Griffith's, with one exception: tenants with a holding valued at less than £5 annually were exempt, but their landlord was liable for the tax. This liability was a powerful incentive for landlords to get rid of smaller tenants in any way they could and certainly contributed to the wave of evictions that took place throughout the second half of the nineteenth century.

Why was Griffith's carried out?

It arose from the first requirement of any taxation system, an actual basis in reality. The only taxes in general operation in Ireland in the early part of the nineteenth century were based on property: taxpayers were required to pay a proportion of the annual value of the property they occupied (i.e. the notional income the property should produce over a year). Obviously, the first question posed by any sensible taxpayer is Who values the property? The answer in early nineteenth-century Ireland was the local Grand Jury, invariably composed of the largest property-owners. Unsurprisingly, the valuations they produced were deeply suspect, riddled with exemptions and varying widely from county to county.

The Act of Union of 1800 had made Westminster directly responsible for governing Ireland, a task that was virtually impossible without clarity about the most basic lever of any public administration, the tax base. So the key to getting to grip with Ireland was to produce a consistent island-wide valuation of property.

If there was one thing the Victorians were good at, it was measuring things, but they found Ireland tough going. The production of the valuation took almost 30 years, from the early 1820s to the late 1840s. The first steps were to map and fix administrative boundaries through the Ordnance Survey and the associated Boundary Commission. The next step was to assess the productive capacity of all property in the country in a thoroughly uniform way. Richard Griffith, an English geologist based in Dublin, became Boundary Commissioner in 1825 and Commissioner of Valuation in 1830.

Understanding the Valuation and Maps

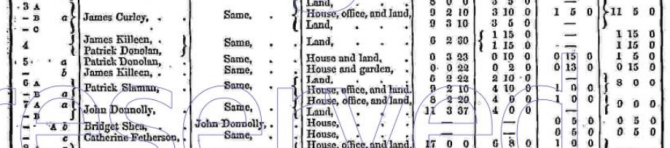

On Griffith's Valuation, the numbers and letters of reference to the maps are the connection between the Valuation and the accompanying Ordnance Survey map; they appear on the left of the Number and Letters column on the original pages of the Valuation. In general, each townland is surrounded by a thick line on the map, with the numbered subdivisions outlined with lighter lines. The numbers represent a lot number, that is to say, a single area outlined on the Ordnance Survey map and labelled with that number. Capital letters after the subdivision number (e.g. 2A, B ,C) are used to label subdivisions within a lot and indicate separate parcels of property in the townland held by the same individual. For example, if a John Kelly rented two separate fields in the townland of Ballymore, these will be listed within the townland under his name following each other as 2 A, B. It follows that the order of the personal names within each townland does not imply geographical location: the fact that two names appear beside each other does not mean that the individuals were neighbours. The number represents only the order in which the valuator listed each holding in his manuscript field book.

The same capital letter can appear more than once within the same numbered lot when the location of cottagers' or labourers' houses is being indicated. Lower-case letters after the holding number (e.g. 2a, b ,c) indicate a single property held in common by a number of listed occupiers. This was common in rural areas in early and mid-nineteenth century Ireland, especially in the West, with anything up to 20 families farming an area in common. Lower-case italic letters are used to indicate built structures, including houses. The order in which these lower-case letters appear is significant: where cottagers' or labourers' houses are included within the limits of a farm, the farmer's house is labelled a, while the cottagers' houses are labelled b, c.

It should be noted that the connection between the maps and the Valuation is never perfect; there are regular omissions and mistakes. The best connection is in the working copies of the maps used in the Valuation Office itself. In the example above, John Donnolly is occupying lot 7, subdivided into A and B, with a house and office labelled a within 7A. Then, also within lot 7, Bridget Shea's holding is labelled - A b, meaning her house is separate from John Donnolly's, but is also within 7A.

Local Numbers and Names

These generally appear in urban areas, where there is street numbering, and appear on the right of the Number and Letters column. Unlike the map reference numbers, they do imply that those listed beside each other were actually neighbours. The large double column includes all the personal and place names recorded by the Valuation.

Townlands and Occupiers

This is by far the most complex sub-column. In urban areas, it may be headed Street etc. and Occupiers.

For rural areas the name of the townland is given centrally, with the number(s) of the Ordnance Survey sheets on which it appears immediately underneath. There may also be further geographical information, sub-terrace names in towns, small village names in the country.

Under the geographic names comes the list of occupiers. It is very important to keep in mind that this is just a list of economic occupiers of the associated properties, not a list of heads of household. Nonetheless, this is the only part of the record that will sometimes record family information. In areas where a surname is particularly common, it is not at all unusual for more than one individual of the same name to be recorded as the occupier. Where this happened, the valuator was required to add some distinguishing information, an agnomen. This could be an occupation (John Kelly, tailor), Junior or Senior to distinguish father and son, or most usefully, a patronymic, John Kelly (Mike) and John Kelly (Pat) indicating that the father of the first John Kelly is named Michael and that of the second Patrick. A number of other agnomens are also sometimes used, but do not convey family information.

Where there are multiple separate lodgings in a building, the name of the immediate lessor is entered in the occupiers column, with lodgers in brackets. This happens most frequently in urban areas, for obvious reasons.

Immediate Lessors

It is very important to be aware of the precision of the Valuation's terminology: 'immediate lessor' simply means the person from whom the occupier named in the adjoining column was leasing the property. The word 'immediate' is used because long chains of letting and subletting were common. In fact, it was more usual for the immediate lessor to be a middle-man of some sort that the outright owner of the property. So 'immediate lessor' is not the same as landlord.

Other terms sometimes used in this column are:

'Reps of', an abbreviation for Representatives of, indicating that the individual named was dead at the time of the valuation and his or her legal interest in the holding was being represented by a family member or by an executor;

'in Chancery', meaning that the property is the subject of a legal dispute;

'in fee', meaning that the occupier is also the legal owner of the property;

'free', meaning that the occupier has no lessor, but no formal legal title, in effect squatting.

Description of Tenement and Area

This is an extremely terse description of the property being valued. 'House' covers all buildings used permanently as dwellings, as well as public buildings; 'Office' is used to describe factories, mills and farm outbuildings such as a stable, turf shed, cow barn, corn shed, or piggery.

From a genealogical perspective, the most important aspect of this column is whether or not it includes a house. Because the aim of the Valuation was to record economic occupation, it is perfectly possible for one individual to appear multiple times: if John Kelly is renting a field in Ballymore, another field in Ballybeg and a house and land in Ballymuck, he will appear in the occupiers column for all three places. However, the description column will record 'Land' in Ballymore and Ballybeg, and 'House and Land' in Ballymuck. It is a fair assumption that the family home is in Ballymuck. It is extremely important to keep this in mind: since the database name search is only for names, and not types of property, it is all too easy to assume that a search has shown three John Kellys, rather than the same one three times. The area of land held is given in Acres, Roods and Perches. There are 40 square Perches to a Rood and four Roods to an Acre.

Rateable Annual Valuation

Land, Buildings, Total

The taxable (or rateable) value was the income that the property could reasonably be expected to produce in a year. For buildings, the construction materials, age, state of repair, and dimensions were factors taken into account. For land, the soil quality, average rents, aspect, and distance from market were all taken into account.

Why is Griffith's Valuation important for Irish genealogy?

The focus of the Valuation was taxation, not family or demographic information, and any genealogical or local historical information it supplies is purely incidental. So why is it of such importance for Irish research?

The simple reason is the destruction of The Public Record Office of Ireland in 1922. The Office had been part of the Four Courts complex for more than five decades when, on April 13th 1922, forces opposed to the Treaty with Britain occupied the entire compound. The occupation aimed to be a direct challenge to the authority of the Provisional Government by paralysing the centre of legal administration for the entire island. It continued for more than two months as both sides struggled to avoid direct confrontation.

The time was put to good use by the occupying forces in organising their logistics. In particular, for their munitions dump they chose the most heavily built and therefore the safest part of the complex, the strong room of the Public Record Office. On June 28th, under intense pressure from the British government, the Provisional Government began an assault. After two days of shelling, a number of huge explosions destroyed the Public Record Office. Fires started as a result of the shelling had ignited the stored munitions and the destructive force of the blasts had been magnified by confinement within the reinforced walls of the strong room. A giant mushroom cloud rose over the city. Everything in the strong room was destroyed.

The returns from 1861, 1871, 1881, and 1891 had already been destroyed by official order, so the biggest loss was the 19th-century census returns of 1821, 1831, 1841 and 1851. If these had survived, Griffith's would be a footnote in most research; as things stand it is the only comprehensive, or near comprehensive, account of where people lived in mid-nineteenth century Ireland. It covers over a million dwellings, and nearly 20 million acres, recording around 80% of the population. Because the Valuation was published (and has long been out of copyright) it is by far the most widely available record used for Irish research.

Our thanks to Ask About Ireland for their contribution to this article.

Surname Search

The information on this website is free and will always be so. However, there are many documents and records that we would like to show here that are only available for sale. If you would like to make a donation to the Lurgan Ancestry project, however small (or large!), to enable us to acquire these records, it would be very much appreciated. We could cover our pages in Goggle Ads to raise money, but feel that this would detract from the information we are trying to provide.

You can also help us to raise money by purchasing some of our ebooks on our sister website: www.genealogyebooks.com

The Lurgan Ancestry Project is a not for profit website, all monies raised from the site go back into it. Genealogy Ebooks is our sister website and takes payments on our behalf.

|